- Home

- Ken Saunders

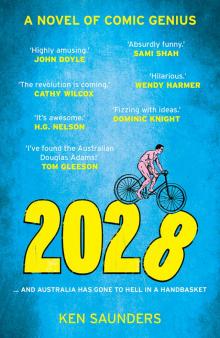

2028

2028 Read online

‘This is not quite how Peter Dutton imagines our dystopian future: crap technology, paranoid spies, cycling activists and even dumber politicians. Set phasers to stupid. Hilarious.’ –Wendy Harmer

‘Ken Saunders waddled about the 2028 National Tally Room as the results came in. He has seen the future! Relax! It’s awesome!’ – H.G.Nelson

‘If Douglas Adams wrote The Killing Season, it would be as absurdly funny and worryingly prescient as this!’ – Sami Shah

‘It’s a state of peak technology, peak focus group, peak surveillance. But the revolution is coming—and it’s off-line, naked and riding a bicycle.’ – Cathy Wilcox

‘A highly amusing, if grim, forefeel on how politics will be plagued in the near future.’ – John Doyle

‘A hilarious and horrifying vision of a future where parking meters are pokies and nothing’s scarier than Australia Post. Saunders’ novel is fizzing with ideas that are troublingly plausible.’ – Dominic Knight

‘I’ve found the Australian Douglas Adams! Imaginative and very funny stuff.’ – Tom Gleeson

First published in 2018

Copyright © Ken Saunders 2018

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to the Copyright Agency (Australia) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

ISBN 978 1 76063 106 2

eISBN 978 1 76063 698 2

Set by Midland Typesetters, Australia

Cover design: Hugh Ford

Cover image: iStock

To Flo, Laurie and Marina

Three generations of inspiration

Contents

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

CHAPTER ONE

Renard Prendergast eased the car into an available parking spot, but as he reached for the door, Autocar clicked in and straightened out his parking attempt. Normally, Autocar only took over when a vehicle was in danger; however, several months earlier, Renard had accidentally set his Autocar feature to ‘Correct all’ and didn’t know how to turn it off. Renard didn’t much care for driving, yet every time Autocar intervened, he felt diminished. Though he held an office-based data-analysis job, deep down he felt that, as an ASIO agent, he ought to be able to drive like James Bond. Autocar clearly thought he couldn’t.

Renard inserted his credit card into the Parkie and opted to play for two dollars. Brisbane City Council had been the first local government to introduce Parkies, but now they were everywhere, even in this inner-city suburb of Glebe in Sydney. They brought, in a limited way, poker machines to the streets. Motorists still had to pay for parking, but now got one play in return, a chance to hit the jackpot. Parking meters had been transformed into something they had never been before: popular. The Parkies had proven a windfall for councils. Even pedestrians stopped to play the meters and many motorists readily paid/played for more parking time than they needed.

The machine made a few cha-ching sounds before lighting up with: Congratulations! You have won five minutes of free parking. Double or nothing? Renard punched No. Who would play double or nothing for five minutes? He started a new round. This time the parking meter chimed a tinkly rendition of the 1812 Overture finale. Renard stepped back in surprise.

‘What did you win?’ a pedestrian called out, she and her dog both stopping to look.

‘I don’t know,’ Renard stammered. ‘I’ve never won before.’

They peered at the screen of the parking meter and a ripple of disappointment passed through them. He’d won only fifty dollars. ‘I’d have thought the 1812 Overture would be for a five-hundred-dollar prize at least,’ the woman commented. ‘I’m told if you win a thousand, it plays “Girls Just Want to Have Fun”.’

‘What if you’re not a girl?’

‘The Parkies have face recognition software,’ the dog walker replied.

‘Do they?’ Renard asked. He knew full well they did. The Parkies were one of the wearying sources of information he routinely examined in his work. The thing about metadata was its meta-ness.

‘Sure they do,’ the woman continued. ‘Remember how a Parkie helped catch the Strathfield bank robbery gang? Though the guy driving the getaway car put a stolen credit card into the parking meter, the Parkie itself was still able to identify him. Funny attitude to try to pay for parking while your friends are sticking up a bank. A chance to win, I suppose,’ she mused philosophically. ‘He should have worn a balaclava like the rest of the gang. Actually … I think it plays “Money Changes Everything” when you win a thousand dollars. That would make more sense.’

Renard squinted at the Parkie. It was still offering to play double or nothing. Renard was not going to push his luck. He pressed the button and one clean fifty-dollar note emerged from the machine.

The woman raised her eyebrows. ‘I didn’t think anyone under thirty used cash anymore.’

‘I’m eating at Low Expectations tonight,’ he explained. ‘No cards accepted.’

‘I should have guessed when you chose cash,’ she replied. ‘I go there every so often. God knows why.’ She and her dog set off down Glebe Point Road.

Low Expectations had been his first assignment with the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation. Well, not his first assignment, but his first and only out-of-office assignment. This was eight years earlier, a year after he’d joined the organisation. A new director had been appointed, someone unlike any of the long-term spooks in ASIO’s upper echelons. This one had hit the agency with public relations and team-building ideas never before contemplated. ‘You need to be a people person to head a security agency,’ he had told the cameras on his appointment, ‘and our agents need to be so too.’ He had launched, in the year of the same name, ASIO’s ‘20:20 Vision’. He wanted the data analysts to get out of the office one day per week to get a feel for the public they spied on—to ‘get touched’, he said, adopting a catchphrase popular back then. It was not a complete break with tradition; ‘meeting people’ was still to be done in the traditional ASIO way of infiltrating groups, planting listening devices and intercepting messages whenever possible. The regular workload of the data analysts stayed the same, mind you, but now they had only four office days per week to do it. The initiative, just like the ASIO director himself, had not lasted the year. The data analysts had proved remarkably inept, leaving fingerprints where they should not have and, in the case of the Lustathon incident, landing ASIO utterly in the soup.

Renard’s 20:20 Vision assignment had been Low Expectations, which had come to ASIO’s attention precisely because it wasn’t coming to their attention. ASIO wanted to know why. Officially, Low Expectations was a bookshop/cafe, yet it sold only Charles Dickens novels and all the stock was second

-hand. The inside was decked out in what Renard termed ‘Industrial Revolution chic’: a few tables were scattered between the even fewer bookcases, while at the back, several teenagers toiled over contraptions that appeared to be working looms. There were teacups on some tables and a smell of food. On his first visit, Renard rashly ordered a cappuccino.

The owner scowled. ‘You can have tea,’ he rumbled, in a tone that indicated Renard ought not to ask for cinnamon chai.

The tea was weak and Renard understood why when he witnessed the owner reusing the tea bag for subsequent orders. There was only one item on the menu. Renard ordered a bowl of gruel.

The reason for ASIO’s interest was that Low Expectations had absolutely no online presence. It wasn’t just that it had no website and no social media accounts—it had no wifi. In an era when virtually no one carried money, the shop didn’t accept credit cards. The owner kept his accounts handwritten in ink in large nineteenth-century-style ledgers. There wasn’t a laptop, a Genie phone or a Gargantuan in the place. Their only concession to modern times was that they had electricity—used sparingly, to judge by the temperature of the tea.

Any business with so low a profile must be hiding something. Renard was tasked with finding out what. However, as Renard dutifully pointed out in report after report, he found nothing to report. He could discover no subversive activities and no answer to the still more perplexing question: how could an enterprise with such an appalling business model survive?

The owner employed a gang of local teenagers to work the looms after school. Although they did their best to appear downtrodden, Renard discovered that they were paid the standard award wage. All the employees dressed in nineteenth-century clothes or nineteenth-century rags, depending on their roles. The owner sold what cloth was produced, but the quality was not high. Book sales were minimal. Customers were permitted to read novels from the shelves while having tea and gruel. The owner kept the gruel bubbling all day. Upstairs, where the new-fangled electricity flowed more generously, they ran movies and TV adaptations of Dickens’ novels. A large, threatening sign on the front door indicated that customers were not allowed to use mobile phones or any electronic devices while in the shop, and when Renard tried surreptitiously, he found some sort of jamming device prevented signal reception. Despite appearances, someone in the place had technical savvy. As far as his efforts at eavesdropping went, he overheard nothing beyond local cafe chitchat and one person snivelling over the fate of Little Dorrit.

The adolescents on the looms looked the part of surly, malcontent labourers, and on Renard’s first visit, one of them lifted his wallet. Renard found it necessary to protest vigorously before the owner reluctantly compelled the youth to produce the wallet. The owner then proceeded to take the lad off ‘for a thrashing’. Renard was left with his gruel and the shrieks from out the back. Later, at the office, he viewed the ‘thrashing’ from a CCTV camera in the laneway behind the shop. There he saw the owner and the kid laughing and having a drink of something, with the pickpocket emitting periodic howls and pleas for mercy. What sort of business operated by training your staff to pick the pockets of the customers?

His immediate supervisor at ASIO back then dated from the romantic Cold War era, when spies spied on spies and filing cabinets had secrets worth stealing. He thought Low Expectations might be a front for something and told Renard of a photography shop that the Soviets operated in Melbourne in the 1970s. The two Soviet spies filled their shop window with dreadful wedding photos: people with their eyes bugged out or looking as though they had something stuck in their teeth. The Soviet agents wanted to work without being disturbed. The photos were there to make sure they weren’t bothered by customers.

For ASIO in the 2020s, those glory days of spy-versus-spy were long gone. Now the spy service defended against terrorists: addled young men who blew themselves up in public places or lonely fourteen-year-old boys locked in their rooms hacking into the electricity grid for no particular reason. With opponents such as these, ASIO was perpetually on guard and there could never be a point of victory. ‘In the old days,’ his supervisor reminisced, ‘when we successfully turned their double agent into our triple agent, there was a moment of triumph to something like that.’

Though he was no longer required to, Renard continued his surveillance of Low Expectations. He always went on his own. It wasn’t a place that could be shared with friends, let alone with a date. And he continued to spy. He’d once stolen a letter from the box where people could leave and pick up mail. (Low Expectations had introduced this service after Australia Post abandoned letter delivery in 2022.) This stolen letter, he hoped, would finally reveal whatever was going on in the shop.

The letter had been not only harmless but inane. It was a load of Elizabeth Bennet-style trivialities about who would be attending some upcoming dance, who was wearing what and who had said what to whom. He was pretty sure he knew who wrote it: one of those Jane Austen types who had begun frequenting the place. They often sat there in their bonnets writing away. Their frivolousness annoyed him. What business did they have being in a Dickensian workshop?

That was when he realised that he actually liked Low Expectations.

Now, with his fifty-dollar Parkie win in his hand, he pushed open the squeaky door. The looms were mostly quiet, and only Kate, one of the friendlier of the teenage textile labourers, was there. In her two years working in the shop, her cloth work had become skilled.

The owner came over to Renard. ‘Gruel?’ he asked and, after Renard nodded, added a surly, ‘Tea as well, I suppose.’ Renard took a copy of Bleak House from the shelf and searched for where he’d left off. Did it even matter? The first forty pages were about it being foggy and little else. Eight years ago he hadn’t liked Dickens novels. He wasn’t sure he liked them any better now.

The owner was back with a large, badly chipped bowl full of gruel. ‘There’s a letter for you,’ he announced.

‘A letter?’

‘Yes, a letter. Your name is Ned, isn’t it?’

Renard’s shock could not have been greater. ‘Yes,’ he managed.

‘It looked like you weren’t too sure about that answer,’ the owner observed suspiciously.

‘It’s just—’ Renard paused, thinking fast ‘—how did you know I was called Ned?’

‘You told me your name was Ned when you first started coming here.’

‘Ah, y-yes …’ Renard stammered, reaching for the letter that the owner now seemed reluctant to give to him. ‘My name is Ned … It’s just that no one has called me that for a very long time.’

The owner considered this for a moment, then finally handed over the envelope.

A letter for Ned. A letter that had been nine years in the coming. ‘No one has called me Ned,’ he repeated, his heart beating faster, ‘for a very, very long time.’

…

Autocar was a business with a single product, normally a Darwinian vulnerability in the fickle world of technology. Autocar could stave off extinction only through the most demanding of juggling acts. Its niche was in a tiny crevice of public and political indecision and, to survive, it had to nourish that indecision. Autocar was still thriving for the moment. Everyone who wanted to drive a car needed its product; indeed, it had been mandated by legislation to be installed in all motorist-operated vehicles still on Australian roads.

The history of software companies was littered with success stories that led to the abyss. One moment, everyone would be salivating for a company’s product; the next, no one wanted it at all. Autocar was attuned to this perilous environment. Despite its enormous success, it was perpetually primed to shut down the business the next day, if necessary. It rented no offices and had no inventory to speak of. The only ‘premises’ it kept was space on a server located in Collinsvale, Tasmania—Collinsvale being the Australian town with the lowest annual temperature, hence the lowest air-conditioning costs for the server. All Autocar employees worked from home and had what was called in t

he industry a ‘no ripcord clause’: your future redundancy money was included in your fortnightly pay. You could be tossed out of the plane without a parachute at any moment, but at least you had been paid all your entitlements.

The opportunity that Autocar had wedged open was society’s inability to come to grips with the benefits of the driverless car. In its first five years, the driverless car had achieved only a 37 per cent market share. Those vehicles obeyed the rules, gave way when it was correct to do so, slowed in wet conditions. In other words, they behaved like complete chumps in the minds of certain motorists still behind the wheel who didn’t obey the rules or give way and who sped past other cars in thunderstorms. Knowing that driverless cars never drove aggressively and the passengers in those cars were probably doing Sudokus or sleeping, motorists asserted themselves with greater and greater abandon. Thus, while driverless cars never hit other driverless cars, the motorists out there hit driverless cars, they hit cars driven by other motorists, they hit pedestrians and cyclists and they hit lampposts. In looking at the data, it was clear to everyone that the lampposts were not the problem. The obvious response, at least to the pedestrians and cyclists recuperating in hospital, would have been to ban the motorist car. But nothing was that simple.

Seventy years of relentless car advertisements, of sleek vehicles streaking alone across the outback or ascending to the apex of some steep mountain where no car had any proper reason to be, had left an imprint on part of the population. For them, driving was a right. Driving was freedom. Admittedly, that freedom was sometimes hard to perceive, but those motorists knew it was there, if only they could roar along that deserted outback road instead of being mired in traffic on the Western Distributor. They weren’t giving all that up without a fight. To the hard core of the motorist faction, most of whom couldn’t help but have a Y chromosome, the driverless car was for wusses, uncoordinated gits and women. Legislators feared to antagonise so large a group of voters, but nonetheless motorists, like the cigarette smokers before them, were going to have to make concessions.

2028

2028